Gist of the experiment

There is now plenty of evidence that evolution can be a rapid process. Understanding how rapid evolutionary processes occur in nature is of utmost relevance to investigate adaptation to rapid climate change, which has already been documented for many species at the level of phenological and distribution range shifts (Parmesan & Yohe 2003; Franks et al. 2007; Charmantier et al. 2008; Hoffmann & Sgro 2011).

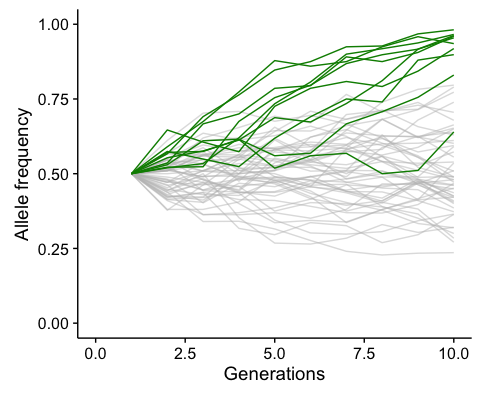

Last century’s breakthrough in evolutionary theory amounted to the focus on genetics as the basis of evolution and the redefinition of evolution in terms of allele frequency changes (Figure 1), influenced by neutral as well as selective forces (Fisher 1930; Wright 1942; Huxley 1942). Nowadays, well within the genomic era, our challenge is to experimentally demonstrate and extend those works by monitoring changes in allele frequencies in evolution experiments over multiple generations and selective environments in nature (e.g. Elena & Lenski 2003).

Allele frequency trajectories in a simulated Wright-Fisher population under drift and with 10 alleles naturally selected

With this aim, we are setting up a coordinated distributed experiment in which populations of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana consisting of c. 200 sequenced ecotypes (1001 Genomes Consortium 2016) will be sown into replicated plots in different sites around the globe. By incorporating many sites with a broad range of environmental conditions, from southern Spain to the Scandinavian arctic, and by tracing the ecotype composition over multiple years by means of sequencing, we aim to gain insight into the roles of environmental variables in shaping temporal dynamics and spatial variation of population genomics.

We will apply pool-sequencing of plants throughout their reproductive stage to identify successful ecotypes, their phenological timing, and their genomic makeup. As predicted by local adaptation theory, we expect that success under certain temperature, moisture and soil composition will be related to the environment of origin and phenotypic characteristics of each ecotype. However, in contrast with other common garden experiments, we will directly measure the dynamics of natural selection and adaptation to each of the environments where the experiment is taking place.

Exemplary evolution experiment plot with Arabidopsis thaliana plants

Exemplary evolution experiment plot with Arabidopsis thaliana plants

The Protocol

You can find the general GrENE-net protocol here.

Photo of the study site in Tubingen, Germany (2017)

Photo of the study site in Tubingen, Germany (2017)

Policy and ethics statement

Read the full policy and ethics statement here.

Note on post-experiment handling of genetic material:

Uncontrolled transplant experiments can lead to genetic contamination of local populations (Rogers & Siemann 2004; Saltonstall K 2002) and to species invasions (Seebens et al. 2017). Although A. thaliana is a cosmopolitan plant native or naturalized to all countries where GrENE-net experiments are carried out, we ask participants to grow their replicate populations in a controlled area, preferably an institution’s ground, free from natural A. thaliana populations. Furthermore, after the experiment all used soil and plant material will be incinerated and a treatment herbicide will be used in a secured perimeter to eliminate any trace of planted seeds, as has been done before in similar outdoor experiments (Exposito-Alonso et al. 2017; Exposito-Alonso et al. 2018).

References:

- 1001 Genomes Consortium (2016) 1,135 genomes reveal the global pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 166: 481-491.

- Parmesan C & Yohe G (2003) A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421: 37-42.

- Charmantier A, McCleery RH, Cole LR, Perrins C et al. (2008) Adaptive phenotypic plasticity in response to climate change in a wild bird population. Science 320: 800-803.

- Elena SF, Lenski RE (2003) Evolution experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and genetic bases of adaptation. Nature Reviews Genetics 4: 457-469.

- Franks SJ, Sim S, Weis AE (2007) Rapid evolution of flowering time by an annual plant in response to a climate fluctuation. PNAS 104: 1278-1282.

- Fisher RA (1930) The genetical theory of natural selection: a complete variorum edition. Oxford University Press.

- Hoffmann AA, Sgro CM (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470: 479-485.

- Huxley JS (1942) Evolution: The Modern Synthesis.

- Wright S (1942) Statistical genetics and evolution. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 48: 223-246.

- Rogers & Siemann (2004) Invasive ecotypes tolerate herbivory more effectively than native ecotypes of the Chinese tallow tree Sapium sebiferum. J Appl Ecol 41:561-570.

- Saltonstall K (2002) Cryptic invasion by a non-native genotype of the common reed, Phragmites australis, into North America. Proc Nat Acad Sci 99:2445-2449.

- Seebens et al. (2017) “No Saturation in the Accumulation of Alien Species Worldwide.” Nature Communications 8 (February): 14435.

- Exposito-Alonso et al. (2018) “Spatio-Temporal Variation in Fitness Responses to Contrasting Environments in Arabidopsis thaliana.” Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13508.

- Exposito-Alonso et al. (2017) “A Rainfall-Manipulation Experiment with 517 Arabidopsis thaliana Accessions.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/186767.